|

| The androgyne Rebis from Splendor Solis, Solomon Trismosin, painted copy from the British Library, London. |

Georgie Hyde Lees joined the Stella Matutina, sponsored by W. B Yeats, and taking the magical name of 'Nemo Sciat' ('Let no-one know'). A few years later, in 1919, Violet Firth joined Alpha and Omega taking her family's motto—'Deo Non Fortuna' ('By God, not by Fortune')—as her magical name and she went on to write under a streamlined version of it, 'Dion Fortune'. In due course, she also went on to found her own magical order, The Fraternity of Inner Light, and had a significant influence through her prolific writings, both fiction and books esoteric topics, including The Mystical Qabalah (1935).

One of her earliest works is entitled The Esoteric Philosophy of Love and Marriage. It was written in 1924, and if readers can get past some of the imperialist, Anglocentric, and homophobic elements of the presentation, it is a valuable insight into ideas of sex and gender at the period in the groups related to the Golden Dawn. Indeed Moina Mathers accused Fortune of 'betraying the inner teaching of the Order'—a charge she was able to rebut (the relevant teachings belonged to a level that she had not yet reached; see Nevill Drury, Stealing Fire from Heaven: The Rise of Modern Western Magic, 129).

Ideas of Gender

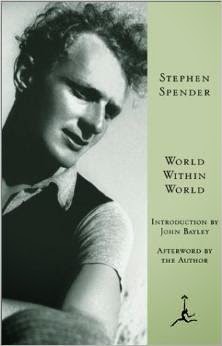

The Esoteric Philosophy of Love and Marriage is a short book and much of it focuses on occult polarity, gender, and sex. Fortune writes of the spiritual human as having two aspects: a timeless self or "individuality", which progresses through incarnations (cf. Yeats's Principles), and part of this is manifested in a particular incarnation as a temporary self or "personality" (cf. Yeats's Faculties).Esoteric science... conceives [the spiritual human] not to be sexless, but on the contrary, bi-sexual, and therefore complete in himself. The individuality is two-sided positive and negative, has a kinetic aspect and a static aspect, and is therefore male-female or female-male, according to the relation of "force" to "form" in its make-up. The personality, however, is one-sided, and therefore has a defined sex. The individuality may be thought of as a magnet, having a positive and a negative pole, one of which is at a time is inserted in dense matter, and the nature of the pole inserted determines the sex of the body that is built up around it. (The Esoteric Philosophy of Love and Marriage, 31)The timeless self therefore embraces both male and female in a form of alchemical union, where the two elements remain distinct though joined.

The bisexual or androgyne as envisaged in alchemy is almost never a sexless fusion of female and male, but a union of female and male as the androgyne (Greek: andros-man and guné-woman), or less commonly hermaphrodite (Greek gods, Hermes and Aphrodite). It is often referred to as the 'rebis', re (thing), bis (twice), indicating its explicitly double nature, and the alchemists usually show their rebis with two heads (female and male) and often with both female and male genitals.

|

| Michael Maier, Atalanta Fugiens, Emblem XXXIII, engraving by Matthäus Merian, the Elder. |

Hermetic Principles

What Fortune calls 'esoteric science', taking on the language of the modern age, is more traditionally referred to as 'Hermetic wisdom' and traced back to the Corpus Hermeticum and the teachings attributed to Hermes Trismegistos.Anna Kingsford, founder of the Hermetic Society in the 1880s, had similarly seen a fundamental sexual balance, as expressed in the Hermetic principles underlying the universe: 'The Hermetic system [is superior to pseudo-mystical systems] in its equal recognition of the sexes'. This included both duality and gender as fundamental forces. Her introduction to the Hermetic dialogue The Virgin of the World, entitled 'The Hermetic System and the Significance of its Present Revival', offers a summary of some of the fundamental principles of Hermetic thought. She notes the fundamental unity of all things in Spirit, but that this is not incompatible with 'an original Dualism, consisting of principles inherently antagonistic'. Hermes Trismegistos tells Asclepios in The Virgin of the World that 'this law of generation is contained in Nature, in intellect, in the universe, and preserves all that is brought forth. The two sexes are full of procreation, and their union, or rather their incomprehensible at-one-ment, may be known as Eros, or as Aphrodite, or by both names at once', seems to lie behind Yeats's 'Supernatural Songs', such as 'Ribh Denounces Patrick' and 'Ribh in Ecstasy'.

Mary Greer has drawn attention to how Kingsford's formulations foreshadow the later and now better-known axioms of the Kybalion (1912). There is no evidence that Yeats knew The Kybalion, but he certainly knew both the Hermetic Corpus and the contemporary interpretations of it, such as Kingsford's. And, despite the importance of Cabala and Rosicrucianism to the teachings of the Golden Dawn, it was called a Hermetic Order and at least one of its cover names was the 'Hermetic Students', as recorded in Yeats's autobiographies and on the invitation to his initiation.

Human and Daimon

Anna Kingsford posited that 'Every human spirit-soul has attached to him a genius, variously called, by Socrates, a dæmon; by Jesus, an angel; by the apostles, a ministering spirit'. She explains that, ‘The genius is linked to his client by a bond of soul-substance’ and ‘is the moon to the planet man, reflecting to him the sun, or God, within him.... the complement of the man; and his "sex" is always the converse of the planet's' (The Perfect Way, or the Finding of Christ [1882], 89–90).The Yeatses' Daimon, as outlined in the automatic script and in A Vision A, similarly complements its human counterpart, "(the Daimon being of the opposite sex to that of man)" (AVA 27, CW13 25). The Daimon is not just a companion moon to the human planet, but closer in fact to the bar magnet imagined by Dion Fortune.

Within physical life and normal contexts, the Daimon manifests through the people and habits of life—sexual relations, love for the other, all the complex knot of relationships and desires. Yeats imagines the Daimon or Guardian Angel conspiring with sweetheart and also jealous of her (AVB 240, CW14 175), referring to the western horizon or 'the seventh house of the horoscope where one finds friend and enemy' (AVB 213, CW14 157). Yet the Daimon also represents both the individual's destiny and the highest possibility of free will.

In many respects, Yeats increasingly came to see the Daimon as the complete archetype from which the localized human is a fragment immersed into space and time to become manifest and experience phenomenal reality. Trying to formulate the relationship between human and Daimon in one draft, Yeats wrote:

Though it enters into memory & reflects in the human mind, it is not contained within that mind nor can that mind see the whole object as it is present before the daimon. though sometimes, it knows of it, through its own increasing excitement. & sometimes it shows some perception of the daimon in such a way, that the perception seems miraculous by seeing it separated from the general framework of its thought, as in prevision, & clairvoyance & those affinities of personality which are so swift that different personalities seem to coexist within our mind. Though for the purposes of exposition we shall separate daimon & man & give to man a different symbol, they are one continuous<consciousness> perception, seeing we perceive all that the daimon does & only remember & therefore only know what is in part a recurrance of our past.

(NLI MS 30,359, probably written in Cannes, December 1927/January 1928)

Certainly connection to the Daimonic aspect of perception or inspiration was something to be sought, particularly by those assigned to Phase 17, Yeats's own phase, the Daimonic person. One of the ways that he could do this was through seeking a female voice, approaching towards the opposite half of the bar-magnet-self.

'a great mind must be androgynous'

In one of the earliest drafts of the system Michael Robartes expounds some of the system, and Owen Aherne makes a comment about remembering a 'passage in the Table talk [of Coleridge], he said that all great minds were androgynous' (‘The Discoveries of Michael Robartes’, typescript, YVP4 43). Aherne goes on to make a conjecture about the system of A Vision that is incorrect, but Virginia Woolf also seized upon this comment of Coleridge's, and explored it perhaps more richly and aptly:

Key elements that echo Yeats's own ideas are those of fusion and a mind that uses all its faculties—one of the elements of Unity of Being, where on one Faculty brings the others into play automatically. When writing of Unity of Being Yeats uses the image of sympathetic vibration, Woolf here of resonance, but the porousness that allows the undivided mind to express itself and more of itself than is normal is part of the symbolic androgyne. Within A Vision and elsewhere in Yeats's writings, the term Unity of Being changes meaning and application as Yeats's ideas developed, but it was always something that the person should aim for, an ideal of the mind.Coleridge perhaps meant this when he said that a great mind is androgynous. It is when this fusion takes place that the mind is fully fertilized and uses all its faculties. Perhaps a mind that is purely masculine cannot create, any more than a mind that is purely feminine, I thought.... Coleridge certainly did not mean... that it is a mind that has any special sympathy with women; a mind that takes up their cause or devotes itself to their interpretation.... He meant, perhaps, that the androgynous mind is resonant and porous; that it transmits emotion without impediment; that it is naturally creative, incandescent and undivided. In fact one goes back to Shakespeare’s mind as the type of the androgynous, of the man-womanly mind.... (A Room of One's Own, Ch. VI)

The conjecture that Aherne makes is that 'If we understand the Primary nature as masculine the saying would apply very well to those phases as you have described them' (YVP4 43), which is wrong because in the Yeatses' system the primary is feminine and the antithetical masculine, but the vital thing is that all minds are an equal mixture of both tinctures. Whichever side of the Wheel Will and Creative Mind are on, Mask and Body of Fate balance them equally in the opposite tincture. Only perhaps those who achieve Unity of Being are able to fully realize this equal oppostion in a form of dynamic equilibrium, Coleridge's androgynous great minds, but the fundamental elements are there in all humanity.

|

| Two sample dispositions of the Faculties. (a) a person with Will at Phase 4, and (b) a person with Will at Phase 17. (See A Reader's Guide to Yeats's 'A Vision', p. 116, Fig.7.4.) |

Too many critics, perhaps, take this comment as license to identify the Daimon with any and all of the women in W. B. Yeats's life (and little else), but there is definitely an element of truth in the idea that the Daimon and its influence are discerned in these women, not least George Yeats.The Will and the Creative Mind are in the light, but the Body of Fate working through accident, in dark, while Mask, or Image, is a form selected instinctively for those emotional associations which come out of the dark, and this form is itself set before us by accident, or swims up from the dark portion of the mind. But there is another mind, or another part of our mind in this darkness, that is yet to its own perceptions in the light; and we in our turn are dark to that mind. These two minds (one always light and one always dark, when considered by one mind alone), make up man and Daimon, the Will of the man being the Mask of the Daimon, the Creative Mind of the man being the Body of Fate of the Daimon and so on. The Wheel is in this way reversed, as St. Peter at his crucifixion reversed by the position of his body the position of the crucified Christ : “Demon est Deus Inversus”. Man’s Daimon has therefore her energy and bias, in man’s Mask, and her constructive power in man’s fate, and man and Daimon face each other in a perpetual conflict or embrace. This relation (the Daimon being of the opposite sex to that of man) may create a passion like that of sexual love. The relation of man and woman, in so far as it is passionate, reproduces the relation of man and Daimon, and becomes an element where man and Daimon sport, pursue one another, and do one another good or evil. (AVA 26–27, CW13 24–25)

In A Vision, the system's myth of itself is that it is the product of the Daimons of W. B. and George Yeats—that is WBY's female Daimon and GY's male Daimon (— with possible contributions from the Daimons of the children, Anne and Michael). Indeed, though the supposed instructors worked through a hierarchy of communicating spirits, one of the voices, Ameritus, was said to be George's Daimon (YVP2 300).

There is thus a complex interchange of man and woman sitting and writing questions and answers, or the man questioning the sleeping woman, yet it is the Daimons of the two who supposedly originate, and they influence their own charge directly but also work through the spouse. Male and female are fused and yet distinct, androgynous.

|

| Michael Maier, Atalanta Fugiens, Emblem XXXVIII, engraving by Matthäus Merian, the Elder. |

The following post will look at Yeats's use of female voices in poetry to express a potentially Daimonic view of reality, and subsequent ones will consider the Daimon with Plotinus and the Golden Dawn, and concepts of Unity of Being.