Artists' Work as their Soul's Essence

(This follows from Patterns of People in the Phases Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV.)

by George Gilbert Scott (1864–72).

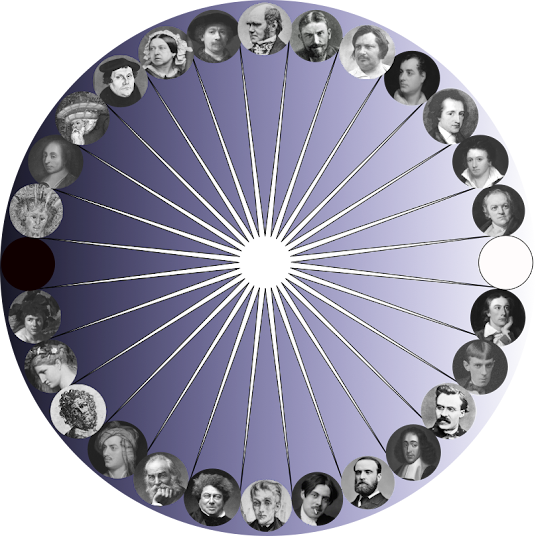

To return to the panoply of poets and thinkers, my observations about the preponderance of artists and the way that they are viewed are far from original. Helen Vendler, for instance, makes very similar comments in the book of her thesis, Yeats’s “Vision” and the Later Plays from 1963, explaining Yeats’s “scheme of literary history,” and noting how the different phases focus on the poets’ aesthetics.

About two thirds of all the examples Yeats chooses to give are literary men; of these, about two thirds are poets. The twenty-eight phases become virtually, in the course of the book, a scheme of literary history, bizarre perhaps, but literary history all the same—and most especially, poetic literary history.

Helen Vendler, Yeats’s “Vision” and the Later Plays, 29–30

Hazard Adams says much the same in The Book of Yeats’s Vision from 1995. He observes that Yeats “sees the writers in or as their work,” and this gives some an indication of what Yeats identifies in each person within the wheel.

Of the forty-eight “examples” specifically cited, thirty-one are what we call imaginative writers and one is a painter; only four (Victoria, Parnell, Napoleon, and Socrates) are not writers of some kind. Yeats sees the writers in or as their work, and as metonyms they are absorbed into fiction much as he is absorbed into the fiction of A Vision.

Hazard Adams, The Book of Yeats’s Vision, 88

And it is not just professional self-regard that makes writers and poets predominate, nor is it laziness that equates artists with their work. Yeats regards artists—at their best, at least—as giving something of their soul's own essence in their work, thus making them clearer and more explicit exemplars of the soul's bias and ways of being. The lineaments of Will, Mask, Creative Mind, and Body of Fate can be traced more clearly because the artists have transferred them into what Yeats terms "phantasmagoria"—the eerie images cast by magic lanterns in a form of proto-cinema—implying that they project their own life in transmuted form artistically.

A poet writes always of his personal life, in his finest work out of its tragedies, whatever it be, remorse, lost love or mere loneliness; he never speaks directly as to someone at the breakfast table, there is always a phantasmagoria. Dante and Milton had mythologies, Shakespeare the characters of English history, of traditional romance; even when the poet seems most himself, when he is Raleigh and gives potentates the lie, or Shelley ‘a nerve o’er which do creep the else unfelt oppressions of mankind’, or Byron when ‘the heart wears out the breast as the sword wears out the sheath’, he is never the bundle of accident and incoherence that sits down to breakfast; he has been re-born as an idea, something intended, complete. A novelist might describe his accidence, his incoherence, he must not, he is more type than man, more passion than type. He is Lear, Romeo, Oedipus, Tiresias; he has stepped out of a play and even the woman he loves is Rosalind, Cleopatra, never The Dark Lady. He is part of his own phantasmagoria and we adore him because nature has grown intelligible, and by so doing a part of our creative power.

Essays & Introductions 509, cf. CW5 204

What the assigned phase of A Vision's pageant is intended to indicate is not the person we might meet in the street but a kind of essence, not “the bundle of accident and incoherence that sits down to breakfast” but the self “re-born as an idea, something intended, complete.” In their work, the poets are “more type than man, more passion than type,” and “nature has grown intelligible.” And this, in part, is the reason why the poets—“in or as their work”—dominate the pantheon of the phases—there is a clarity and intelligibility that is separate from the accidents of personality, opinion, and contingency.

The unique quality of the poet, even over other artists perhaps—the novelist, for instance, may “describe his accidence, his incoherence”—is this expression of something fundamental. As he explained to Olivia Shakespear: “You can define soul as ‘that which has value in itself’ or you can say of it ‘is that which we can only know through analogies’ ” (July [1934], CL InteLex 6074, cf. Letters (Wade) 825). And the soul’s “characteristic act” is being in time or “temporal existence”:

Even though we may think temporal existence illusionary it cannot be capricious; it is ... the characteristic act of the soul and must reflect the soul’s coherence.... We may come to think that nothing exists but a stream of souls, that all knowledge is biography, and . . . that every soul is unique.

Introduction to The Resurrection, Variorum Plays 934–35; Explorations 396–97

Poets may reveal this soul more effectively through their writing, but every person has a soul.

A poet is by the very nature of things a man who lives with entire sincerity, or rather, the better his poetry, the more sincere his life. His life is an experiment in living.... it is no little thing to achieve anything in any art, to stand along perhaps for many years.... to give one’s own life as well as one’s words (which are so much nearer to one’s soul) to the criticism of the world.

“The Friends of My Youth” (lecture draft, 1910), Yeats and the Theatre, 74

This is part of what Yeats had told Moina Mathers he was looking for in his involvement with the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in the dedicatory introductions to A Vision A in 1925:

I wished for a system of thought that would leave my imagination free to create as it chose and yet make all that it created, or could create, part of the one history, and that the soul's. . . . What I have found indeed is nothing new, for I will show presently that Swedenborg and Blake and many before them knew that all things had their gyres; but Swedenborg and Blake preferred to explain them figuratively, and so I am the first to substitute for Biblical or mythological figures, historical movements and actual men and women.

(AVA xi–xii, CW13 liv–lv)

The other representatives of the phases may not have the opportunity to project so fully or clearly as the poets, but also in their own ways are regarded as expressing their essence in their work and life, not in every accident and detail, but in an overriding quality or mood that, for instance, Yeats considers to make a Shakespeare like a Napoleon like a Balzac. We have no work by which to judge a "mute inglorious Milton" and lack of deeds leaves a "village-Hampden" unknown, as well as a "Cromwell guiltless of his country's blood," as Thomas Gray saw in his "Elegy in a Country Churchyard." The selected names have something that expresses their essence clearly and brings them to prominence, and may therefore provide us with a mnemonic figure for their phase.